The Troubled Years in the Borders

by Norman Turnbull

Turnbull Clan High Shenachie

When Will-O-Rule saved King Robert the Bruce’s life in 1313, he would have been part of the Douglas Company, probably a small baron, and maybe even because of his stature and build, Douglas’s champion. He would most likely be in his early 20’s at this point, which means he would have been born around 1290. His father and any older brothers, however, could well have fought along side Wallace at Stirling Bridge and Falkirk in 1297 and 1298, as the Douglases did. It’s a fact that boys as young as 11 did bloody their swords and axes.

In the year 1583, a catalogue of woes arrived on the desk of Sir Francis Walsingham, Secretary of the State to Queen Elizabeth I. It came from Lord Scrope, Warden of the English March, and was a further reminder of the “broken state” of England’s northern frontier. This “compleynt” (complaint) and claim for redress against the Armstrongs was yet another example of a seemingly endless stream of similar “reiffis” (robberies), “murtheris” (murders), “birnyngs” (burnings) and “spoylings” (spoiling) that emanated from the Border.

To Wilsingham, sitting at the hub of government and deeply immersed in affairs of state, such barbaric behaviour must have seemed outlandish indeed. But to the likes of Gynkne (Jenkin) Hunter and Bartame (Barty) Milburn, left impoverished and bereft, it was the grim reality of daily life on the Border Marches. Even their crudely built, defensible homes, referred to in contemporary documents as “bastell-houses,” were a direct result of a continuing legacy of three centuries of warfare, violence, lawlessness and systematic devastation that had left the Anglo-Scottish Border country into a pitiful state.

During the second half of the 13th century peace and prosperity reigned across the Borderland. Sharing a rugged landscape and a similar culture, Border folk of both kingdoms had much in common and lived together in relative harmony. Border towns flourished, merchants and landowners prospered and farmers were able to enjoy the fruits of their labours.

On a national level, however, each nation remained wary of the others’ territorial ambitions and during this period of calm, the English in particular had taken the opportunity to strengthen their Border holds on Norham, Alnwick, Wark and Carlisle, as well as establishing efficient lines of communication along their Northern frontier. When Scotland’s King, Alexander III, was killed in a riding accident in 1286, he died heirless and in the absence of an obvious adult successor to the Scottish throne, the English monarch, Edward I, in furtherance of his plans for the total domination of Scotland, used his influence to install John Balliol on the Scottish throne in1292.

Unfortunate and weak minded, Balliol was forced to recognize Edward as his feudal overlord and by a process of intimidation and humiliation, the English monarch proceeded to rule Scotland by proxy. In time, Edward’s behaviour became so overpowering that Balliol, albeit under pressure from his council, eventually rebelled against him. In an act of defiance, the Scots negotiated a mutual defence agreement, which became known as the, “Auld Alliance,” with Edward’s traditional enemy, France, and proceeded to lay siege to the English fortress at Carlisle.

In a fury, Edward retaliated by launching a series of devastating invasions across the Border. In 1296, Berwick was stormed and in an act of sheer brutality the town’s entire male population was put to the sword, earning Edward the epithet “Hammer of the Scots.”

Recoiling from the initial impact, the Scots soon retaliated with equal ferocity and in 1297, under William Wallace, defeated the English at Stirling Bridge.

As one outrage followed another, the two kingdoms (Scotland and England) became engulfed in a war of attrition that was destined to last for 300 years. The Borderland became their battleground and as the scavenging armies of both nations invaded and retreated across the “line,” towns and villages were put to the torch, their inhabitants slaughtered, crops were looted or burned and vast areas of arable land were reduced to impoverished wastelands. Wallace was later defeated at Falkirk in 1298, but then Robert the Bruce, gathered the Scottish nobles to his cause and crushed the army of Edward II at Bannockburn. Bruce went on to wrested Berwick from English hands in 1318 and his victorious Scottish armies plundered England’s northern shires unopposed, exacting tribute and blackmail from the terrified population.

After Bruce’s death, Edward III defeated the Scots at Halidon Hill and Berwick was recaptured in 1333.

Fifty years later the Scots were victorious at Otterburn and, in 1402, the English had their revenge at Homildon Hill. Although Berwick passed briefly into Scottish hands in 1461, it was retaken and finally ceded to the English in 1482.

Both nations continued to mount sporadic raids and armed incursions that bedevilled the Border country and, in 1513, James IV of Scotland led a large-scale invasion into Northumberland, which culminated in a devastating battle at Flodden Field, his own death and the loss of a significant proportion of Scotland’s no-bility. It was, without doubt, the worst military defeat in Scotland’s history.

Throughout all the former mentioned battles, the Turnbull clan played a big part, as indeed, did all of the border clans. When it came to defending their name and their country never was a thought given to the consequence of life and death. The most important thing was the protection of their name. To have their name taken away they saw as a fate worse than death itself.

For the Borderland, there was worse to come when 30 years later, Henry VIII attempted to contrive the marriage of the English Prince Edward to the infant Mary, Queen of Scots. Having failed to woo the Scots with a mixture of threats and diplomacy, the bellicose monarch attempted to force the union by means of a devastating show of military force and from 1544 to 1549, in a period that became known as the “Rough Wooing,” English armies supported by foreign mercenaries brought “fyre and sword” to the Scottish Lowlands.

In this constant war of attrition, both governments encouraged their Borderers to harass their embattled neighbours across the pine by way of incessant raiding and, even in periods of comparative peace between the two kingdoms, violence along the Borderline continued unabated. Inevitably, such appalling conditions bred a ruthless and resourceful society who had, by the beginning of the 16th century, become “maisterful theeves” and rustlers, skilled in the arts of skirmish, raiding, ambush and extortion-they added the word “ blackmail” to the English language. (It was also recognized that they were by far the finest light horsemen of their day and in times of national conflict, both governments were quick to conscript Border horsemen into their armed forces as scouts or “prickers.”)

Caught up in the vicious cycle of warfare, raiding and reprisal, survival became the most important element in the Border’s uncertain life.

Due to the ever-present threat of sudden violence descending upon him and his loved ones, the Borderer’s well being lay firmly amongst his own clan or “grayne” and his loyalty to his surname invariably overrode any national allegiance. It should also be born in mind that raiding was not confined solely to forays into the opposite realm. Cross-border alliances were not uncommon and in 1525, it was noted that “the Armstrangs of Liddersdaill and the theiffs of Ewysdaill were joined with the rebels of Tyndaill…and kepet all company togedders.” When a suitable opportunity presented itself, formidable war bands such as these were certainly not averse to plundering amongst their own countrymen. As a consequence, even families who shared the same nationality lived in constant suspicion of each other and fickle loyalties led to bitter rivalry, which could suddenly escalate into open hostility and deadly feud.

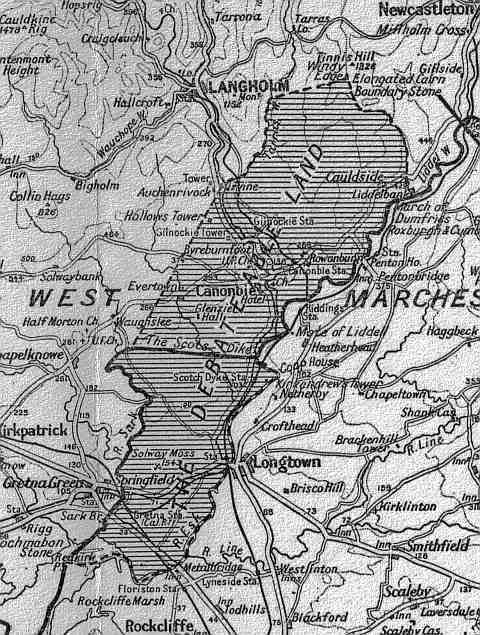

In an attempt to impose some degree of law and order on what had become an anarchic society, both kingdoms had agreed to divide their Border territories into East, West and Middle Marches and appointed wardens and keepers to govern and police them.

Between the west marches of each kingdom, however was a narrow strip of territory known as the Debateable Land. Although both kingdoms hotly contested ownership of this small piece of ground, neither of them was prepared to take responsibility for the crimes of the inhabitants and, so, it became the haunt of some of the most nefarious reiving bands and cutthroats in the Border country.

Amongst his many responsibilities, part of a warden’s duty was to meet with his opposite number on truce days and dispose cross-border justice accordingly. Both governments acknowledged that the standard laws were quite inadequate when dealing with such a violent and unruly populace and as a consequence the unique Border Laws, which specifically governed behaviour across the Border Marches, supplemented those laws.

Legislation covered such criminals activities as aiding and abetting raids into one’s own country, illegal marriage to a person from the opposite realm and the conditions that applied when engaged in the lawful pursuit of stolen goods, known as the “Hot Trod.”

By the beginning of the 16th century, raiding, or “reiving”, had become a way of life and against this background it is hardly surprising that when people built their homes, the

emphasis was firmly on security. Fortified buildings on both sides of the Border ranged from large, well-defended castles to stark, imposing tower houses, fortified manor houses and defensible farmhouses known as bastles, a class of building unique in the British Isles.

In addition, many churches were strengthened against attack and, in times of trouble, served as austere sanctuaries for their congregation.