A life of the great bishop and statesman who founded Glasgow University has never been written. This was probably less a lack of piety on the part of our ancestors than an awareness that even when the scattered facts about Bishop Turnbull were brought together much still remained uncertain and obscure. Death came very quickly to him after he had completed his crowning work, and in the disturbed Scotland of his day his memory rapidly faded . . . We have no portrait of him . . . Perhaps, however, by setting him quite deliberately against the background of his times we may begin to glimpse something of the vision that animated this great teacher, patriot, administrator and churchman . . . in him too we can see, in the very decline of the Middle Ages, something of the pattern of medieval man, a perfect blend of the sacred and secular virtues, equally at home in Church and State.*

A life of the great bishop and statesman who founded Glasgow University has never been written. This was probably less a lack of piety on the part of our ancestors than an awareness that even when the scattered facts about Bishop Turnbull were brought together much still remained uncertain and obscure. Death came very quickly to him after he had completed his crowning work, and in the disturbed Scotland of his day his memory rapidly faded . . . We have no portrait of him . . . Perhaps, however, by setting him quite deliberately against the background of his times we may begin to glimpse something of the vision that animated this great teacher, patriot, administrator and churchman . . . in him too we can see, in the very decline of the Middle Ages, something of the pattern of medieval man, a perfect blend of the sacred and secular virtues, equally at home in Church and State.*

Our William Turnbull was born around 1400, probably in the family of Bedrule. He was described by James II as a blood relation, perhaps through William's mother. Despite the well-documented tendency of the early Tumbulls to raiding and war, William, from an early age was more drawn to the large religious houses in the area: the Cistercians at Melrose, Benedictines at Kelso, and the Augustinians at Jedburgh, from whom he received his early schooling. Sometime before 1416 he was at the University at St. Andrews (where there was an Augustinian house), to whose founder (Henry Wardlaw) he may also have been related through marriage.

At this time the educational environment in Western Europe was in a period of ferment: some two hundred years earlier, Albert the Great had brought the study of nature, through recently re-discovered Arabic Aristotelian thought, into the Christian universities. He introduced his own notion of "experiment" and insisted on the value of observation as a source of knowledge, believing reason and faith of necessity to be in harmony. Thomas Aquinas, his pupil, attempted to reconcile the rationalism of Aristotelian thought with the revealed faith of Christianity. He constructed an entire cosmology that was to be the dominant conception of the world for nearly half a millennium. A somewhat different approach was the more "idealistic" - less "naturalistic" route to the discovery of ultimate truth exemplified in the nominalism of William of Ockham. During Turnbull's time, the faculty at St. Andrews had opted for the Ockhamist approach. Besides, St. Thomas' approach was under some suspicion as having teen capable of misinterpretation by Wycliffe and Hus, early reformers. William however opted for this "Albertist" approach with its greater interest in physical questions; he studied "physics" (cosmology), "psychology" (the structure of human thought) and astronomy, giving birth to his idea of a university, which was finally established some thirty years later, espousing this approach. In all of this, he was a pioneer in education for his time, anticipating the rise of what is called the enlightenment by more than two centuries.

William received the Bachelor of Arts in 1418 and Master of Arts in 1420. Around this time he apparently also became a cleric, perhaps remaining on the University staff while receiving clerical appointments at East Calder near Kelso and later at Hawick. In 1430 he was elected dean of the faculty of arts, but in 1431 he left Scotland for the relatively new University at Louvain, perhaps as a result of plague at home. At Louvain he found himself in a more agreeable "Albertist" educational environment. Here he studied canon law, receiving a Bachelor of Canon Law in 1434.

In order to better understand the dire; ion his life took for the next 15 years, it might help to outline very briefly some of what was happening in the Church in Western Europe at this time: The "Great Western Schism," when for a period of time there were two - then three - factions in the church each claiming to have elected a legitimate Pope, had recently been settled with the election of Martin V by the 12 Council of Constance. However the Council had also declared that the General Council was the supreme authority in the Universal Church and that the Pope must obey its decisions. Thus, pro-conclliarist and pro-papal factions were poised for struggle. The Council of Constance had also decreed that another council be called in five years, a further one seven years after that, and subsequently every ten years. Despite obvious reasons for personal misgivings, Martin dutifully called a Council at Pavia in 1423, which accomplished little other than to lay plans for the next council seven years later at Basle.

In the meantime, Martin died early in 1431 and was succeeded by Eugenius IV, a personally austere and pious man, but more emboldened to assert papal prerogative. When few delegates showed up for the early stages of the Council at Basle, Eugenius, suspicious of conciliar radicals, and disturbed that Hussite representatives had been invited without his knowledge, dissolved the Council and called for a new one to be presided over by himself at Bologna. This caused a storm of controversy throughout Western Europe. Secular rulers were "choosing sides" and among them, James I had decided to send the Scottish representatives to Basle, regardless. (Through the not un-self-serving intervention of the German emperor, Pope Eugenius was eventually persuaded to drop his plans for the Council at Bologna.)

William, who for reasons unknown seems to have been held In high favor at the papal court at this time, perhaps through his connections at Louvain, was sent in 1433 as a personal representative of Pope Eugenius to James I to try to persuade him not to send representatives to the Council at Basie. Over a period of several months James seems to have been persuaded, but by that time the Council at Bologna had been cancelled. Meanwhile, William was appointed by James as royal representative in Rome. I? By 1435 however, he appears to have incurred the displeasure of James I. Perhaps This came as a result of James' opposition to money flowing from Scotland to Europe, and especially Italy, in part because of the number of men like William who were living and studying there; perhaps it came also as a result of James' opposition to papal reservation of church appointments; William was always a strong supporter of the papacy and its prerogatives, for theological reasons undoubtedly, but in part also because he was keenly interested in European unity (again, he was several centuries ahead of his time) and as a loyal churchman would have presumed the Church to be the means to that objective. At any rate, in 1435 William decided to continue his legal studies at Pavia in Italy, receiving a Doctorate in Canon Law in 1439. Here he was once again in an environment of humanist ideas and this excited him and must have brought him to the opinion that education was the way to national unity in Scotland; once again, he would have thought of "his" university to be founded to promote this "fresh approach to the past."

Meanwhile events at home were producing something akin to turmoil. In 1437 James I was murdered and in a minority reign the nobles were engaged in self-serving struggle for Influence and power. William returned to Scotland in late 1439 and by 1441 had become Keeper of the Privy Seal and King's Secretary. Over the next three years he seems to have become a person of consequence «n the royal council and a promoter of harmony between the government and Rome (an anti-Pope, Felix V, had been elected by the Council of Basle meanwhile). William was probably instrumental in keeping the young James II loyal to the legitimate papacy and respectful of the Church's rights at home. In 1447, Eugenius IV died and was succeeded by Nicholas V - in the judgment of some, the first true "Renaissance Pope." He was a great patron of education and a great supporter of William Turnbull. Thus, in the same year, William was appointed Bishop of Glasgow. There was a delay in his actual consecration, but his good standing with James II safeguarded the church finances there until he took over in April 1448. [the nobility were prone to appropriate church finances during the vacancy of a bishopric).

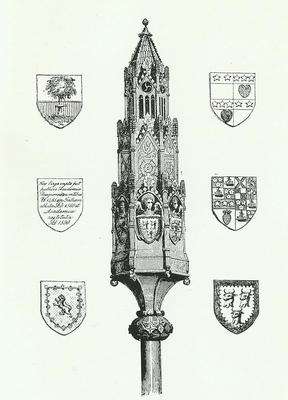

In 1450 at a Parliament at Edinburgh, William was instrumental in bishops being granted protection from interference in their dioceses during vacancies, and in the strengthening of authority of sheriffs over local barons. His extensive study of law was making him very useful to the King! This was also a period of relative "peace" in the country, and left William time for special projects, including the completion of the vestry of the Glasgow cathedral, where his arms were carved in the west wall. Both James II and Bishop Turnbull were now interested in establishing a university at Glasgow. James' interest was two-fold: first, he was concerned about the inadequacy of the baron courts in comparison with the ecclesiastical courts which drew the best-educated men; therefore he was seeking to provide the nobility with the education to act as competent legal officers. And, second, he apparently had a genuinely religious concern for the spread of the true Catholic faith; much of the success of Wycliffe and Hus had been among the poorly educated. William, on the other hand, probably had three - not unrelated - objectives: first, his life-long ambition had been to establish a university governed by collegial principles and dedicated to promoting the "scientific" approach to seeking truth exemplified in the philosophy of Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas. Second, as a canon lawyer, clear thinker and reconciler, he was also eager to promote the teaching of law. And third, he seems to have had an Interest in education as the vehicle to reform of the life of the clergy - a concern of any bishop in any age!

With such unanimity of purpose, it was no surprise when the Papal Bull establishing 15 the University of Glasgow arrived in 1451. And, its initial financial security had been provided for in the previous year - a Jubilee Year. Nicholas V had granted Holy Year privileges (equal to visiting Rome) for visiting the Glasgow cathedral: a donation of ¼ the expense of a trip to Rome was to be divided: 1/3 to be sent to Rome; 1/3 for church rebuilding In Scotland; and 1/3 for the "generality of Catholicism," i.e., for the soon-to-be university.

With the establishing of the University, the Bishop's life-goal was underway. He continued to be active as the King's Secretary at least through July of 1454. These were times of turmoil in the realm between the King and nobility, but the Bishop acted mostly as a reconciler. In mid-1454 he journeyed to Rome, most likely on a routine report to the Holy See (as bishops still must do regularly), and was at a parliament in mid-July. After that, no more is heard of him. He almost certainly died of plague, but even when is a matter of dispute. However it was likely on 3 September 1454, and he was probably buried in the church at Cambuslang, not in his cathedral as would be expected. He may have left the city in an unsuccessful attempt to avoid the plague, which struck the country again that year.

With the establishing of the University, the Bishop's life-goal was underway. He continued to be active as the King's Secretary at least through July of 1454. These were times of turmoil in the realm between the King and nobility, but the Bishop acted mostly as a reconciler. In mid-1454 he journeyed to Rome, most likely on a routine report to the Holy See (as bishops still must do regularly), and was at a parliament in mid-July. After that, no more is heard of him. He almost certainly died of plague, but even when is a matter of dispute. However it was likely on 3 September 1454, and he was probably buried in the church at Cambuslang, not in his cathedral as would be expected. He may have left the city in an unsuccessful attempt to avoid the plague, which struck the country again that year.

What was Bishop Turnbull like? The scanty facts of his life don't say much explicitly, but leave room for an educated guess. He strode through a very tumultuous time in both Church and Kingdom, apparently with such a degree of serenity that he was well recognized as a healer and reconciler. He was not only respected (and used) by both James I I (the young King relied heavily on his judgment and ability) and the Popes Eugenius IV and Nicholas V - both great men in their own right and supposedly inclined to see and make use of greatness in others. And the Bishop literally "spent" his life - wore out prematurely [even for these days, early 50's was still the "prime of life"] working tirelessly trying to bring about harmony in both Church and Kingdom, all the while pressing steadily on towards the fulfillment of his 16 cherished personal goal: the university.

The bishop's generosity to the King in the dark early days, his ability to work with other men . . . are factors in the rise of prosperity and the establishment of peace in James II's reign . . .His espousal of reform at the same time as his unswerving loyalty to the Holy See, his international standing, all are imponderables in the history not only of Scotland but of Europe. The answer to many of the problems of the next century and ours is to combine the old wisdom and the new learning, remembering that both come from "the fountain of all truth and grace." To gain that wisdom for his generation was the aim of Bishop Turnbull, for, as the preamble to the Glasgow [University] statutes goes on to say, "to know it is truth, to love it is virtue and to embrace it the highest goal of man."

The Living Legacy of Bishop William Turnbull

The Turnbull Catholic Society at the University of Glasgow.

The first item is Turnbull Hall, part of the University of Glasgow. Like all type of religious societies connected with an educational institution, it has a Chapel and Canteen as well as a Ministry and social events.

Turnbull High School

St. Mary’s Road, Bishopbrigs, Glasgow

A Comprehensive secondary school serving the surrounding community with approximately 700 pupils and 48 teachers.

*Much of the biographical information, and the opening and closing quotations, are from an article, "William Turnbull, Bishop of Glasgow" by Mr. John Durkan, in the Innes Review of June 1951.

See also: Address about Bishop Turnbull given by Sir William Fraser, Principal University of Glasgow

By: Father William David Turnbull

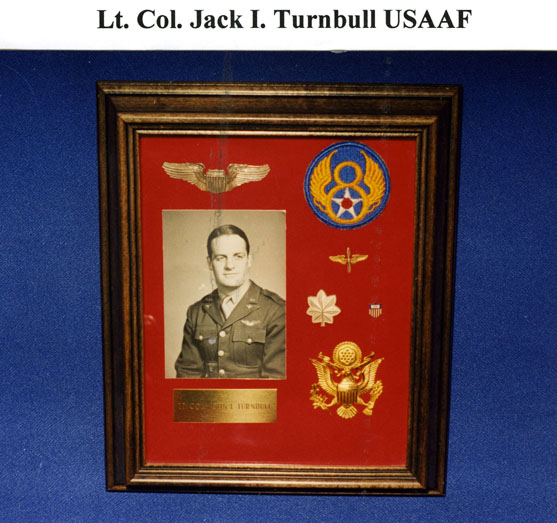

.jpeg#joomlaImage://local-images/tcalibrary/museum/vmpeople/John%20I%20Turnbull%20(Jack).jpeg?width=960&height=1169)

.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/tcalibrary/museum/vmpeople/Malcolm_Turnbull_PEO_(cropped).jpg?width=656&height=960)