As told by John Rodney Turnb ull: John Colclough Turnbull, my father, was born in 1852 down near Rice Lake, 20 miles South of Peterboro in Ontario, Canada. They were a large family – William, John, Albert Leonard, Carrie, Myra, Annie and all were tall, hardworking Christians.

ull: John Colclough Turnbull, my father, was born in 1852 down near Rice Lake, 20 miles South of Peterboro in Ontario, Canada. They were a large family – William, John, Albert Leonard, Carrie, Myra, Annie and all were tall, hardworking Christians.

All the family went west to Manitoba except father. Each man finally owned a square mile in Manitoba near Hartney and Brandon and each woman married a farmer in the same area.

John stayed at home and gave to his parents every dollar he earned till he was twenty-one. For that I believe he was unusually blessed of God. Certainly he was more successful in business than any of them and outshone them spiritually, too.

And so our father went to nearby Port Hope with his parents’ blessing where he worked as a clerk in a grocery store. Then he invaded the county seat Peterboro. In a few years he owned the largest general store in Peterboro on the strategic corner of George, the main street, and Simere. Later, his Turnbull General Store was bought and rebuilt by the Robert Simpson Company of Toronto renown. All of us boys worked in father’s store. I went on Saturdays for 10 cents a day and my pay increased to the magnificent sum of 50 cents.

The very large market was only a block away. The folks from around father’s birthplace brought their dressed fowl, eggs, butter, etc. to market and after selling their products came to father’s store. To induce trade he bought excellent tea in Toronto, blended it himself with other good tea and sold it for 25 cents a pound. The clerks took their sales money to the cashier’s office in the center of the store to get their receipts and charge. Later the metal containers shooting along overhead wires were installed.

Father knew how to get a crowd. I laugh yet when I think of the Saturday he filled the big front windows with lovely calico cloth and sold it at 5 cents a yard (his cost). The store filled jam-packed tight with charming ladies intent on getting that cloth. The clerks couldn’t get through to the cashier. I was the emergency squad. I would take the money and sales slips from the clerk and then duck down right under the elbows of the surrounding ladies and finally emerge at the cashier’s desk! In an hour all the bales of cloth were sold and then father reaped a harvest from those who lingered to buy other wares.

Father could not countenance religious intolerance and when the church where he was a deacon got too pugnacious he bought a lot on George St., paid for most of the lovely little church built on it called Bethany and had a lawyer protect it for all time as a place where all sincere Christians would be welcome. My uncle Harrison was a stern, godly elder there. He was a real Scotch “Sandy” with side burns and loved us children. His dignity was for church!

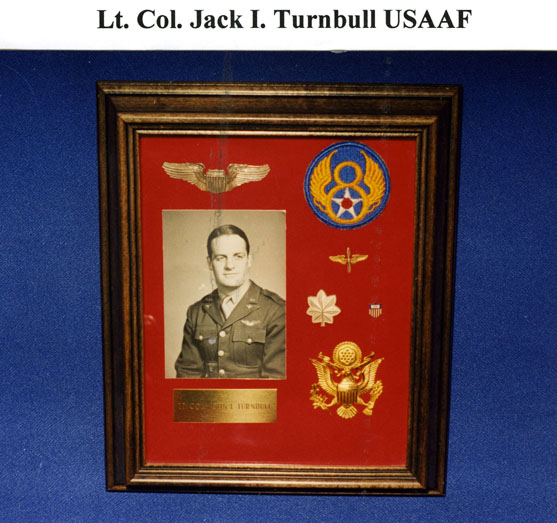

From the little church 25 went as missionaries to various countries all over the world. Three of them were Turnbulls – Louis, Walter, and myself John.

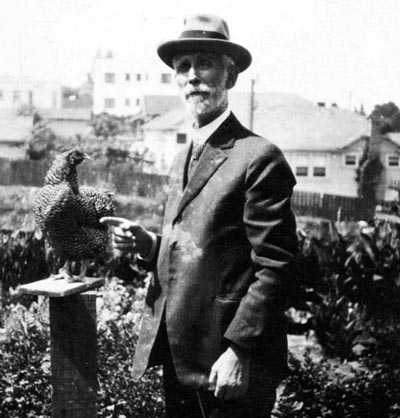

Our father, John C. Turnbull, was passionately fond of trees, flowers, and gardens. To satisfy this propensity he bought a farm three miles West of Peterboro, (Peterborough), Ontario, Canada. It had everything. He was supposed to get one third of the products, but always the poor tenant kept most of the crop. In 1880, when I was born in the big house at 603 Stewart Street, corner of Dublin, on a hilltop, we always had barrels of apples in the cellar in winter. In the summer it was a joyful outing, to climb the cherry trees with a juicy purpose and then munch green peas in the garden, popping them out of their pods, with the resultant unpleasant gastronomical reaction and a persistent tummy ache.

We lived on top of a high hill overlooking the little town (20,000), at the corner of Stewart and Dublin Streets. In winter we could sleigh ride “belly flopper” on individual sleighs down East on Dublin but the favorite ride was the much longer one down Stewart. This was the main road out to the country and the police often chased us off for our own safety but we always managed to avoid the actual clutches of Constable McGinty, a real Irishman that could run like a deer. We had rides for 6 at a time, too on a “bob sled” two sleds, with a board between.

McGinty nearly enmeshed some of us in the net of the law one Halloween night. A larger unthoughtful boy encouraged some of us smaller fry to roll a cart, loaded with ashes, down a steep hill a few blocks away. It got out of control and went hurtling into the ditch. McGinty suddenly appeared and fortunately took after the main instigator who dodged him while we little culprits scurried for cover like young partridges.

Everybody skated on the canal near the big lift locks, once highest in the world, and the pet project of our mother’s brother, long a member of parliament in Toronto of happy memories. He lived to be over ninety.

Christmas was a grand and glorious day at our house. We had a big tree, presents galore but not large, and candy in abundance that should have lasted a month but it disappeared in two days and left an aftermath of headaches. Mother’s dreadful cure was senna leaves brewed into a most abhorrent concoction that made us loathe to admit we felt squeamish.

As the youngest I was thoroughly spoiled by Bill and Walter. When I was just learning to read I was happy to receive for Christmas a lovely big book by Dickens with pictures and stories for children. Bruce (4 years older) and I slept in a high backed wooden bed. Christmas morning I was up early for we had hung our stockings that year at the big open hearth in the sitting room. I couldn’t find my little trousers and grew impatient in hunting for them. Finally I went around behind the head of the bed. Walter and Bill had made a bag of them buttoning them up and trying the bottoms of the little legs. This bag they had stuffed with little presents, nuts and an orange. How they laughed when I found my trousers, and that was typical of their jokes, plenty of good cheer mixed with mischief.

When snowy winter gave way to spring showers our scratchy woolen underwear (how I abhorred it) was discarded and we made long hikes in search of early flowers, May flowers (Hepaticas), trailing arbutus, trilliums both white and red, blue, yellow and white violets and many other treasures found in Jackson’s woods.

Two miles down the C.P.R. tracks, which to my small feet seemed like half-way to Toronto, we knew a place where we could gather wintergreen leaves to chew and even found berries, too.

Education was funneled into our young heads by very strict but capable teachers at the West Ward School, Central School and in Bruce’s case at North Ward, too. Bruce passed first out of that school, the star student.

When I was in kindergarten at Central School, Walter was in high school next door and on the lower side of the hill, separated only by a high wall. He and Bill came to the kindergarten barred window to greet me. I was making a little chair out of toothpicks and soaked peas while they were wrestling with algebra and ancient history.

Across the road was a big park where the band played martial music in the summer time and made the blood stir in our spines. Teacher took us wee things out there for a picnic. I remember the day Queen Victoria had her diamond jubilee and when she died. We got a half-holiday.

Walter was heavyset and as healthy as an Arabian gazelle. He was not built for racing but won five pounds of mixed candies in the sports (Field Day) and we all helped him to celebrate the honor. He came in third in a foot race, but he came in first in many, many other events of his life!

Summer was the time of greatest enjoyment. Before and after father shipped us off to the island at Soney Lake a hundred pleasures awaited us. By night all the boys of our area (about 20) gathered under a big basswood tree a block away. From there we cruised off in games, football by moonlight in Lawyer Moore’s big pasture field, Hunko, run-sheep-run, throw the stick and other games. If we were lazy we just sat and Dave Hooey, who seems to have heard all the Irish jokes of that day, regaled us with the latest jokes about Pat, Mike and the Englishman. I remember many of them yet.

Pat was assigned the job of staying at the wheel of the ship while the rest of the crew slept. The captain told him just to keep the ship pointed towards a certain star. Pat dosed off and when he came to, the star was out of sight. He woke the captain up and said: “Captain please pick me out another star. Faith and begorrah, I’ve passed that other one!”

The other sailors were making fun of Pat and so he thought he would show them that they didn’t know everything. Taking a piece of rope he asked a sailor how many ends does a piece of rope have. “Why two of course Pat. Anybody knows that, you blockhead.” Pat said, “Here is one end and here is a second end, and” throwing the rope overboard he said, “now my wise fellows there is a third end of it, bejabbers.”

On extra hot days we went swimming both morning and afternoon at “The Quarry” in Jackson Park, two miles from home. The route lay down the hill to the West, past the big tree where we stopped to munch “haws” (fruit of the hawthorn tree). Jackson Park was capacious, big enough for a Sunday school picnic. We entered it at the corner, paused to see if there were any beech nuts under the big trees, sauntered among tall pines on a well kept path, passed a pretty little artificial lake (too deep for small boys). But I swam across it at night with Walter and Bill swimming on either side to keep up my courage.

The Quarry had evidently been just that, many years before, but in our time we undressed in the woods and jumped off the bridge that had a dam under it. The water was only about six feet deep at most, an ideal place for boys to cool off. Then we had little fishing rods and would catch chub but never took them home as I can remember.

The C.P.R. tracks to Lindsay were a stone’s throw away. A big freight train would occasionally come thundering by and we could count the cars. A mile or two farther out the tracks was a second deep-water swimming hole. Beside it was a very tall butternut tree, which took skill to climb. We would pick them when still a little green and store them away until wintertime. Then we would crack them before the grate in the sitting room while the snow raged outside and would watch the blue flames from the big chunks of coal in the fireplace.

In that cozy room was a black horsehair sofa. Father worked hard and deserved his success. He was the only merchant that was able to sell out at the age of about 45 and live a semi-retired life for the next 43 years. He went to Heaven at 88. He would come home from the store at noon, have his lunch, lie down on the couch and be asleep in two minutes; get up after 20 minutes of sound sleep and walk back to the store.

In that same room we had family prayers. I learned to read by sitting on father’s knee and spelling out the big words in the Bible. Teacher augmented my vocabulary with lesser words like cat, rat, hat.

The parlor was separated from the sitting room by a large arch with sliding doors. There was a grand piano. When I was five, mother let me have a big birthday party. I invited every boy and girl I knew and there were scores of them. What a happy memory. One of the older girls that came to help mother picked me up and passed me around for the big girls to kiss. I squirmed like a restless panther in a cage to regain my freedom. That party was the biggest that ever graced our happy hilltop. I had another when I was seven, but, growing more cautious with advancing age, I did not invite so many ladies!

The kitchen was large. Mother fed tramps there. None was sent away hungry. One wrote “Sweet Tommy” on our gatepost, a code notice to all other knights of the open road that our place was an extra hospitable abode. In winter mother would pull out the big tub and give an unfortunate man a chance of a bath. Some of father’s extra underwear would go away with him. Mother surely lived up to the motto of Paul, “Given to hospitality.”

Drinking water came from the well pump in the backyard and soft water from the cistern under the kitchen. In the kitchen all of us boys put our hand to making taffy (and in winter cooled it in the snow) and to roasting ears of corn that surely hit the spot when treated with butter and salt.

The side verandah had lattice and in the corner of the yard next to the verandah was a grape arbour where we all knew when the fruit was ripe. A lovely thick lawn of grass surrounded the big white brick house in front and on both sides with old trees along the fence line – elms, birch, and a wonderful maple tree in the corner which I could climb to the very top in jig time.

We had two barns, a neat red one up the lane half a block where we kept “Fly” (the mare), a cow and chickens. The old barn adjoined the house, out of sight but convenient and connected by a woodshed. Walter and Bill cut holes in the eave of the “house” barn so that the wrens could make their nests.

In the newer, red barn a host of activities kept the youth of the neighborhood well informed that the Turnbull boys were alive. A circus in full bloom was quite a triumph. A strong rope was extended across the big room generally graced by the buggy and Walter M. Turnbull gave quite a dramatic exhibition of the latest technique in tight rope walking. It did not matter that he tumbled off when only half way across for there was no yawning chasm of the Niagara gorge below him. Those big brothers of mine had initiative, ingenuity, and Tabasco sauce in their make up that kept folks a-nodding.

Bill and Walter each tried to hold me standing upright on one hand. That Herculean circus stunt they just could not quite complete. Another exploit proved too hazardous for my liking. They stood down below the door by which hay was pitched up into the loft and told me to jump from the second floor into their arms in the lane outside the barn. I debated that one for some minutes before taking off into thin air. They misjudged my agility for I would have gone right over them if Louis had not been standing behind them and all three grabbed me. I did repeat this high trapeze exhibition once or twice but was very sure as to where I was going to land.

Our bedsprings were held up on the wooden beds by loose slats that occasionally dropped out to the floor with a bang, especially during a pillow fight. There was a large poem on the wall that began, “I’m a little pilgrim.” The words were good but the piety expressed was rather mild in comparison with the wild scenes that boyish enthusiasm sometimes created. We did not give way to this pillow hassle frequently for mother laid down the law in her loving way, but while it lasted the pillow war was some contest!

Walter’s budding genius was encouraged by  a picture he saw in a magazine for curing a bad cold. Bill had a cold. The ad showed a man sitting in a box with his head sticking out. A sweat bath applied in the box by oil heat was supposed to chase the cold into the next county. Walter had Bill sit on a cane bottomed chair wrapped him voluminously in heavy quilts. Then he introduced a coal-oil (kerosene) lamp into the scene and lit it with the wick turned down low. “How does it feel Bill? Can you stand it a little higher?” Gradually the heat was increased under Bill. Suddenly with a yell like a Sioux Indian, Bill rose straight into the air. When the debris had been cleared away, the following results were observed. A neat hole the same size as the top of the lamp chimney had been burned through the cane bottom of the chair and a hole of the same dimensions had been burned through Bill’s thick nightgown. The rise in his temperature was not measured but I think the increase above normal was considerable. In due time his cold disappeared.

a picture he saw in a magazine for curing a bad cold. Bill had a cold. The ad showed a man sitting in a box with his head sticking out. A sweat bath applied in the box by oil heat was supposed to chase the cold into the next county. Walter had Bill sit on a cane bottomed chair wrapped him voluminously in heavy quilts. Then he introduced a coal-oil (kerosene) lamp into the scene and lit it with the wick turned down low. “How does it feel Bill? Can you stand it a little higher?” Gradually the heat was increased under Bill. Suddenly with a yell like a Sioux Indian, Bill rose straight into the air. When the debris had been cleared away, the following results were observed. A neat hole the same size as the top of the lamp chimney had been burned through the cane bottom of the chair and a hole of the same dimensions had been burned through Bill’s thick nightgown. The rise in his temperature was not measured but I think the increase above normal was considerable. In due time his cold disappeared.

Many are the happy memories of summers spent at the Lakes. In 1885 when I was five years old, father packed the whole family off. We went by train 10 puffing, clanging, and tooting joyful miles to Lakefield (Ontario, Canada). Then a little steamer, the Innika, took us up the lake, through the gushing lift locks into Clear Lake, then Stoney Lake to the little island.

Later father bought the 16 acres, Ivanhoe Island, on the right in Stoney Lake, a summer paradise. Father worked hard. He saw little of the island himself – just a day once a month maybe, but he surely gave his family a healthy summer.

All of us brothers learnt to swim. Bill was the hilarious one. Louis was quieter; Walter was the intelligent, planning daring young devil, always up to mischief. To tease poor Mother one would fall out of the punt with his clothes on and the other two would jump in fully clothed to rescue him.

Ivanhoe and the other small islands around it are rather fished out now, but at the end of the 1800s we caught plenty of bass, perch and sunfish galore. The doughty muskellunge were few but father was elated to catch one in the early morning, trolling while one of the Triumvirates – Louis, Bill or Walter, rode the skiff.

We all adored pie. The island blueberries were prolific. Mother had an amazing sense of humor. In a moment of parental generosity she promised to make each of us a whole blueberry pie and did. Bill, show-off, ate his too quickly to win and race and ran for the pinewoods to hide his sudden seasickness, to return amid the ridicule of Louis and Walter.

There was a swing between two tall pines and we soared towards the sky on that swing. Wild flowers abounded in the woods.

At the “point” we hunted for “red cedar” logs to whittle. We caught big frogs there too, with a piece of red cloth for bate, and Mother gave us friend frogs legs as tasty as any on the menu of a high class restaurant.

We had a nap after lunch (I still do) swam, rowed to other islands, and climbed up a ladder in the corner of the dining room to sleep gloriously in beds near the shingles of the peaked roof, where occasional thunder storms brought the refreshing rains with a welcome merry noise.

My tormenting elders (they didn’t bother me much except in wholesome mischief) thought one day they would play a fine trick on me. I was sitting on the dock in my bare feet with bamboo poles to try my luck at fishing. They had a big dead fish. To distract me they asked me to do something. They put the dead fish on my line. When I returned from the errand they called out excitedly that I had a fish on my line. I saw at a glance that it was dead, half dried out from being out of the water. They told me to take it to Mother, which I did. They kept me running back and forth and the rascals would put the same old fish on my line. I just grinned to myself and let them think I didn’t know! Mother finally intervened. She wouldn’t let them tease her baby boy.

Big Island lay half a mile away, opposite Ivanhoe. We went there for blueberries too. Walter swam over to it. Nobody lived on it. Beyond Big Island, about two miles from Ivanhoe, was a cool spring at Sandy Bay. We got drinking water there and also at a farm in another direction, a mile away.

.jpeg#joomlaImage://local-images/tcalibrary/museum/vmpeople/John%20I%20Turnbull%20(Jack).jpeg?width=960&height=1169)

.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/tcalibrary/museum/vmpeople/Malcolm_Turnbull_PEO_(cropped).jpg?width=656&height=960)