In the summer of 1931, Loretta Turnbull, a 17-year-old girl from the United States, was competing for the International Championship of outboard motor racing on Lake Guarda in Italy. The Italian, Spanish and English boats were all large, metal and piloted by men.

In the summer of 1931, Loretta Turnbull, a 17-year-old girl from the United States, was competing for the International Championship of outboard motor racing on Lake Guarda in Italy. The Italian, Spanish and English boats were all large, metal and piloted by men.

In contrast, Turnbull’s boat was “a little job with a little bit of airplane linen on the deck.” It was called “The Sunkist Kid,” a nod to Turnbull’s childhood among the orange groves of Monrovia, California. To most observers, she was a minnow among sharks, but they would soon be witnesses to her world-class passion for speed.

In fact, at one point in the 17-mile race, Loretta Turnbull led her competitors by more than a mile. Until a cylinder began to misfire and her boat slowed. Bad luck. The young girl stopped the boat and began to replace “the bum plug.” While she worked, four of her competitors roared by. The repair made, Turnbull gave a pull of the rope, started the engine and was back on her way. She caught the first two boats almost at once, the third not long after, and she passed the fourth just three feet from the finish line.

Suddenly, after a display of speed and coolness, a teenager from California was the world’s best outboard motorboat racer. Clad in greasy coveralls, she received her prize from Crown Prince Humberto and Princess Maria, who leaned forward with the trophy so Turnbull would not step on their carpet.

At her next stop, across the Atlantic in a small village in the Finger Lakes, the buzz began. Loretta Turnbull, the international champion, was on her way home to California and stopping in Skaneateles. Racing in the Sunkist Kid, Turnbull would carry the colors of Citrus College in the Intercollegiate outboard motor regatta on June 20, 1931.

Granted, some residents of the Village were not excited. They found the regatta, now in its second year, to be noisy and the crowds an annoyance. Others were delighted with the publicity and the boost to tourism. But in a New York Herald Tribune article, a mechanic sounded a note that will have a familiar ring to today’s Villagers. “This is the first regatta where I could lay down a monkey wrench and come back in 10 minutes to find it still there!”

Much heralded by the Skaneateles Press, the day came. In the first race, against a field of college boys, Turnbull flew out to the lead. But as she readied her boat to round the first buoy, a patrol boat cut across the course and raised a wake. Years later, she told her daughter, Tiare Richert-Finney, that she had only an instant to decide whether to slow down and maybe lose the race, or go for it. “Like there was any question,” her daughter said, laughing.

Loretta Turnbull went for it. As she hit the wake, the Sunkist Kid leapt off the water and did a barrel roll. Or as she put it in 1935, in a radio interview with Al Jolson, “I was way out ahead of ’em and all of a sudden I did a wing-ding.”

At the top of the roll, the Sunkist Kid threw its pilot 15 feet. Turnbull hit the water hard, dislocating her hip and cracking her femur. Dragged down by her coveralls and the tools in her pockets, stunned by the flip and the impact, it was all she could do to keep her nose above the surface of the water. The rest of the field bore down on her. “Fear sort of took over,” she said. Trying to lift an arm to signal, she barely stayed afloat as the other boats roared by, some within two feet of her face.

Luck and her life preserver saved her. Rescuers came to her aid and she was rushed to the Auburn City Hospital in the local ambulance, which was actually a hearse that doubled as an emergency vehicle. At the hospital, a local druggist, A.J. Hoffman, brought her a short wave radio and she was able to listen to the rest of the races. At her bedside, she was awarded a medal for “having come the greatest distance to participate.”

Loretta with hearse ambulance

Loretta with hearse ambulance

On July 7th, after three weeks in the hospital, she began her journey home, chauffeured in the same ambulance/hearse that had brought her from Skaneateles to Auburn. She vowed to return to following year.

She returned to her parents’ home in California. Her father wanted her to quit racing, but her mother supported her desire to continue. Although she would walk with a limp for the rest of her life, Loretta Turnbull did not slow down.

Her spirit had been evident since childhood. Loretta, and her brothers Rupert, Raymond and Byron, grew up in a house called Polk Place in Monrovia, California. Her father, Judge Rupert Turnbull, bought the estate in 1922 and it was the family home for the next 25 years. It was not a quiet home. Loretta and her brothers would go to a movie theater, watch a western, return home, load pistols with live ammo, saddle up and ride through the nearby orchards firing into the air. “They were baaad kids,” her daughter noted.

(The house still stands. Its present owner renamed it Chateau Bradbury Estate and makes it available for weddings, television commercials and location shooting. You can see it in the film Grosse Point Blank, where it “plays” the home of Minnie Driver’s character.)

Loretta Turnbull’s racing career began by accident when she was 13 years old. To keep the teenage girl occupied while the family summered in La Jolla, Judge Turnbull ordered a small boat from a catalog. He was surprised when a racing model arrived. What did they do?

“We put an outboard on it and we went racing,” Loretta said. She ran out of gas in her first race, three times, and finished last. But she stuck with it. Her father hired a rum runner to follow her with gas cans. She got better. She got faster. And in 1931, she became the International Champion.

“We put an outboard on it and we went racing,” Loretta said. She ran out of gas in her first race, three times, and finished last. But she stuck with it. Her father hired a rum runner to follow her with gas cans. She got better. She got faster. And in 1931, she became the International Champion.

After her accident in Skaneateles, she took time to mend. In 1932, she came back. She raced again in Italy, with her brothers. As a “family team,” they brought home two championships, two competitive records and 13 trophies. In California, she took first place in her class at races held during the 1932 Olympics.

Between 1932 and 1935, she raced in events like the Pacific Grand Prix Sweepstakes, the Champions’ Day regatta, and the Southern California Championship. She won the Hearst Gold Trophy (besting 25 men in the running) and the President’s Gold Cup — more than 80 racing trophies in all. She set the World’s speed record for C-Class outboards.

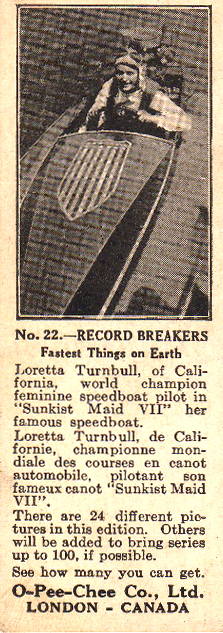

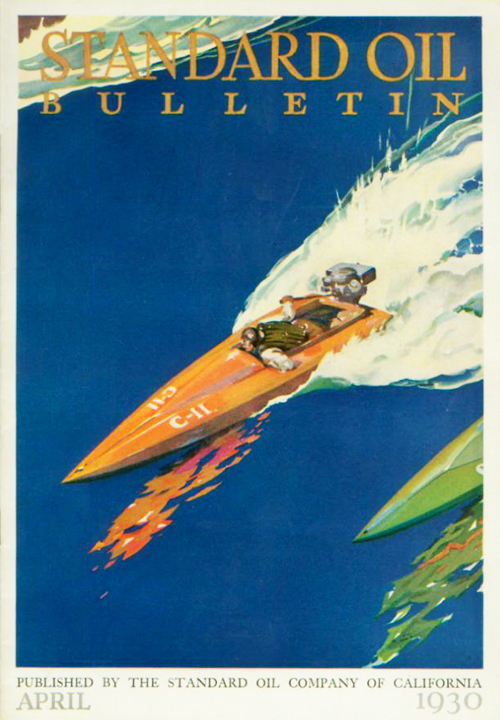

Even without television and People magazine, Loretta Turnbull was famous. She appeared on the back of a Wheaties box, and in ads for Jantzen swimwear and sweaters. She had her own trading card, from Canada’s O-Pee-Chee potato chips. She rode a speedboat of flowers in the Rose Bowl Parade, and graced the cover of the Standard Oil Bulletin.

In 1935, Turnbull teamed with athlete Bunny Seawright in a race across the Catalina Channel; Turnbull drove a speedboat and towed Seawright behind on an aquaplane, a craft variously described as a large washboard or a small toboggan. The ride lasted almost two hours, and the team finished seventh. “I was dead scared of Loretta Turnbull,” Seawright said. “I mean here was a woman who was used to winning and I wasn’t really sure what I was doing.”

That same year, Judge Turnbull bought a 110′ diesel yacht called the Mary Irene and took his family 5,000 miles from Long Beach Harbor to Hawaii. Still competitive, Loretta entered three races at Ala Moana (Ala Wai). She won all three. But her boat-racing days were nearing an end. She married Tom Richert, who had worked as a mechanic on her boats. He became a doctor, established his practice in Hawaii and they began to raise a family.

Loretta “Tetta” Richert was soon the mother of three children, and as many mothers do, she left speed boats behind and began a career as a race car driver. In a 1955 Road and Track article entitled, “Hawaii Races,” she was pictured on a curve with the caption, “Beneath the green Koolau Mountains, Mrs. T.H. Richert, formerly Loretta Turnbull, boating ace of the ’30s, spins her TR-2 in a cloud of dust.” She was the only woman member of the Sports Car Club of Hawaii. “I like to go fast,” she told an interviewer. “I think I will go fast until I die.”

Through it all, she kept her love of the water. She dove for sea shells in Bora Bora, Palau, Tonga, Tahiti, along the Great Barrier Reef and in the Red Sea. A friend recalled diving with her when there were sharks around the boat. She said, “The odds of a shark biting a 67-year-old are remote; I’m going in.”

Through it all, she kept her love of the water. She dove for sea shells in Bora Bora, Palau, Tonga, Tahiti, along the Great Barrier Reef and in the Red Sea. A friend recalled diving with her when there were sharks around the boat. She said, “The odds of a shark biting a 67-year-old are remote; I’m going in.”

Her injury in Skaneateles followed her all her days, and she had hip surgery a number of times over the years. “But when the technology caught up with her, she was off again,” her daughter said. In her early 80s, she went jet-skiing with her sons.

On November 19, 2000, Loretta Turnbull Richert died at the age of 88 in Honolulu. Her family and friends took to the ocean in boats as a final salute, scattering flowers and leis on the water.

“My mother knew Amelia Earhart,” her daughter said. “Amelia was the queen of the skies, and my mother was the queen of the seas.”

In closing, I must mention her daughter, Tiare Richert-Finney, outrigger canoe racer and member of Team O’ahu. In 2002, with five like-minded teammates, she competed in Tahiti and won a gold medal in the International Va’a Federation World Sprints, 1000 meters for women 45 and up. The spirit lives.

Reading the weekly Skaneateles Press on microfilm is like watching a stop-action film. People blink into view and then vanish. So it was with Loretta Turnbull in the summer of 1931. For two weeks, the Press heralded her arrival. The next, they told of her spill and the trip to the hospital in Auburn. The following week, nothing. But Loretta Turnbull had captured my imagination and I couldn’t leave her.

My thanks to the Skaneateles Historical Society and to Tiare Richert-Finney, Loretta Turnbull’s daughter, for her kindness in speaking and writing to answer my questions and share memories of her extraordinary mother. My thanks to Dana Hume Turnbull-Hoyer for additional information on the Turnbull family. The first photo, from Loretta’s daughter, Tiare Richert-Finney, is of Loretta Turnbull in Hawaii in 1935.

This piece was reprinted in the newsletter of the Skaneateles Historical Society, and in the October 2003 issue of The Antique Outboarder.

Other sources: “Loretta Turnbull… expected to arrive,” Skaneateles Press, June 11, 1931; “Miss Turnbull is the only woman entrant,” Skaneateles Press, June 18, 1931; “Injured Girl Racer Doing Well at Auburn Hospital,” Skaneateles Press, June 25, 1931; “Zip Zip Went the Outboards in the 1930s” by Don Stinson, Skaneateles Press, May 8, 1985; Interview with Al Jolson on the Shell Chateau radio show, July 20, 1935; “Hawaii Races,” Road and Track, October 1955; “The Barrier Reef Story” by Tetta Richert, Hawaiian Shell News, July 1983; “Diving for Ships and Shells in the Red Sea” by Tetta Richert, Hawaiian Shell News, March 1986; “Tetta Richert Story” by Carolyn Burke, Hydrofest 1992 (program), October 1992, pp.65-67; “Boat, Car Racer Richert Dies at 88” by Mary Adamski, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 1, 2000; “Going for Gold in Golden Years” by Suzanne Roig, Honolulu Advertiser, March 1, 2002; “Paddlers Coming Home with Two Medals” by Suzanne Roig, Honolulu Advertiser, March 16, 2002

This article by Kihm Winship

.jpeg#joomlaImage://local-images/tcalibrary/museum/vmpeople/John%20I%20Turnbull%20(Jack).jpeg?width=960&height=1169)

.jpg#joomlaImage://local-images/tcalibrary/museum/vmpeople/Malcolm_Turnbull_PEO_(cropped).jpg?width=656&height=960)